Against All Odds and Tradition: Venezuela’s Emerging Football Culture

El Estadio Olímpico Hermanos Ghersi Páez, home of Aragua FC.

Photo: Jordan Florit

One Match in Maracay: even when football doesn't matter, it matters

‘Gloria al Bravo Pueblo!' In Venezuela, every game is anthemic. Penned over 200 years ago by Vicente Salias, a doctor and journalist, the country's national anthem is belted out before kick-off, whether it's a league or cup tie. The players line up, some with their hands to their chest and others with their arms around each other, and the tinny tannoy system or a lone singer stood with a mic stand leads the stadium in a hymn that promises Glory to the Brave People.

As I sat down on the concrete rows of the Estadio Olímpico Hermanos Ghersi Páez, the home of Aragua FC, the rendition was much more sombre and sullen than I expected. Part of the reason was the now permanently low attendances inflicted on clubs across the country by the crippling economic crisis. Even with a stand which was free to enter that day, Aragua struggled to draw a crowd. Even with their hope of qualifying for the Copa Sudamericana on the line, Aragua struggled to draw a crowd. Even though it was potentially their final home game of the season, Aragua struggled to draw a crowd. It doesn't matter if you don't have to pay when you can't afford to get there and back in the first place. It doesn't matter if you don't have to pay when it is dark come full-time and it's a dangerous walk home and you don't have a car. It doesn't matter if you don't have to pay when you have a car, but you can't find a petrol station that hasn't run dry. And with all four of those machinations is the presumption that football would even be on your mind.

To my right was no stand at all, just a wooden scoreboard that would need changing by hand three times over the next 90 minutes, and to my left was the skeleton of what will one day be the stadium's third stand, but has been nothing more than framework for such a while that one fan told me they couldn't recall for how long it had stood unfinished. Across from me, however, was a gentle and restless rumble of red and yellow energy that would burst into life in a matter of minutes. For now, the final lines of Venezuela's call for freedom were sounding out before the main reason for its rather sorrowful delivery would become apparent.

Aragua's opponents that day were Deportivo Táchira and they too had their finishing place to play for. Three days ago, they had flown into the Venezuelan capital of Caracas to avoid making the 10-hour, 700-kilometre journey for the game by coach. While they travelled by air, the 50 or so Táchira fans who had made the behemothic pilgrimage had no option other than to take the road. As well as being an unaffordable method of transport for the majority of Venezuelans, planes were not a reliable method either. For the Táchira players, it did not matter: their President, livestock product magnate Jorge Silva, always made sure one was available and ready for his team to board.

The Táchira fans, for the nearest thing Venezuela has to ultras, were surprisingly lowering their collective sound to hushed and respectable tones. Whatever was causing the atmosphere to unnerve me was uniting both the opposing players on the pitch and the opposing spectators off of it because now the Aragua and Táchira line-ups were mixing up for a joint pre-game photo, and I had noticed that the few ladies who had climbed down the stairs to lean over the barriers were in matching t-shirts with the face of a young man on them. One Aragua player held up a name and numbered shirt displaying ‘Bonilla 11' and a Táchira player did the same but with ‘Bonilla 17' on it. That's when the penny dropped.

Two days earlier, I had been with the Táchira team at their training facility in the city of San Cristóbal, just one well struck goal kick away from their stadium, the Estadio Pueblo Nuevo. Nicknamed El Templo Sagrado (The Sacred Temple), it became apparent it was possibly for more than just its reputation as Venezuela's home of footballing worship. The stadium had large signs on the walls of its catacombic depths with motifs such as ‘God Bless You' and images of Jesus Christ and The Virgin Mary.

El Templo Sagrado del Fútbol Venezuela - Deportivo Táchira.

Photo: Jordan Florit

In the training ground changing room, the locker of former centre-forward Edgar Bonilla had been turned into a shrine. Just under five months earlier, Bonilla had died in a car crash. It happened twenty days before his 24th birthday. A picture of him in full kit, pointing to the sky in celebration and adorned with angel wings, now occupies the space where he once changed. His training kit, a rucksack, and a New York Yankees flat cap still sits in his place, untouched. ‘Por Siempre Aurinegro' a motif reads - Always Gold and Black - the nickname of the club.

The tribute to Edgar Bonilla at his locker in the training ground changing room.

Photo: Jordan Florit

What I was witnessing take place before the game between Aragua and Táchira was a moving tribute from two of his former clubs, and as I glanced over to Maydi, Aragua's press officer and someone who had befriended me during my time in Venezuela, I saw sadness escape her attempts of restraint. This, though, was intended to be a celebration of his life, as much as these things can be, and the players, many of whom were former teammates, smiled for a photo with his memorial shirts.

It was not the first time I had learned of a tragic and premature end to the life of a talented Venezuelan footballer while I was in the country. In Barinas, home to Zamora FC, I had driven past the Estadio Reinaldo Melo, host to the state's second largest club, CD Hermanos Colmenarez. One of nine stadiums either built or remodelled for Venezuela's hosting of the 2007 Copa América, El Estadio Reinaldo Melo is named after the former Zamora FC winger Reinaldo Alfonso Melo Matheus (check out the Copa America logos and Copa America mascots to see what else Venezuela designed when they hosted the tournament).

Having won the Central American and Caribbean Games with the national team in 1998, Melo made his official international debut soon after, in a friendly against Panama. Despite being born in the shadows of Zamora's Agustín Tovar stadium, it was with Universidad de Los Andes FC, Unión Atlético Táchira, and Deportivo Italchacao with whom Melo had his best performances, tallying 121 games and 28 goals in the Primera División in total.

Under legendary national team manager Richard Páez, he was part of the Universidad de Los Andes FC team that won the Segunda División and the Copa Venezuela in 1995, and Richard remembers Melo as a "very skilful and fast winger, capable of playing on either flank." His teammate, Pochi Páez, Richard's younger brother, echoed the sentiments, adding that Melo was "smart and daring - a crack." When it comes to Latino slang, there is no higher praise than ‘crack'. "Above all though, he was a great person."

With Unión Atlético Táchira and Italchacao, Melo competed in the Copa CONMEBOL (now the Copa Sudamericana) in 1997 and 1998, with the return to his boyhood club not arriving until after the new millennium. In the 2002/03 season, however, with Zamora playing in the Segunda División, his professional career was cut short. Falling out with the management over how much time he was dedicating to his studies at the School of Sports Talents, his contract was terminated. At the age of 26, just seven years after his international debut and unable to find a club at short notice, Melo had to retire out of economic necessity.

Four years later, on 2 October 2006, he drove the five-hour journey north-east to Valencia for a job interview with a brewery. He decided to travel back the same day. Just two hours into the return, he lost control of the car on a bend. He crashed it. As a result of his injuries, he lost his life. "We all felt his death," Pochi told me. With the stadium mid-construction, it was named in his honour.

Bonilla's passing has been just as acutely felt in San Cristóbal. He had only joined Táchira in the January and the move marked his own homecoming. He was born in the city in 1995 but had spent his professional career first at Mineros de Guayana and then Puerto Cabello, before his season-and-a-half spell at Aragua.

The players of Aragua and Deportivo Táchira mixing in memory of Edgar Bonilla.

Photo: Jordan Florit

With the tributes and respectful celebrations over, so too were the niceties between the two sides. Ten metres to my left, the visiting fans, among them their barra (a Latin American term for an organised fan group with elements of Ultra, casual, and hooligan culture without being much like any of them), were penned in by metal fencing that itself was manned by a rabble of armed officers.

The men decked out in green, all with very sturdy body armour on and many of whom were armed with rifles and riot shields, were a staple feature of Venezuelan football games. I even saw them at a Friday midday kick-off in the Reserve Cup that was taking place at a training ground with no official seating and fewer than 100 people in attendance. The men were in fact soldiers in the Guardia Nacional Bolivariana, a branch of the Venezuelan military, and the guns they were carrying could have either been FN FALs or AK-103s. The former is a Belgian battle rifle capable of 700 rounds a minute, used in the Cuban Revolution and the Mexican Drug Wars, and the latter is a Kalashnikov-designed assault rifle that has been used in the Iraq War, the War in Afghanistan, and the ongoing Civil War in Yemen. Until 2006, the Venezuelan military had been reliant on the former, but with production of the FN FAL in decline and their cache now aged, they bought 100,000 AK 103 rifles from Russia. The FN FAL, however, has remained in service with the Reserves and the Territorial Guard.

After two weeks of seeing these guns at a total of five live football matches, at random spot checks on the side of the road, and official checkpoints across the country, their presence had become uncomfortably familiar to me. Avalancha Sur, the Táchira barra, were very unlikely to kick off, but if they did, they wouldn't have made it over or around the fence.

The Guardia Nacional Bolivariana were very much out in force.

Photo: Jordan Florit

There had been fan trouble that season, though. On the opening day of the Clausura - the Closing Stage of Venezuela's two-part league format - what began as a peaceful protest by Caracas fans ahead of their home tie with Deportivo Lara became a violent clash with the Guardia Nacional Bolivariana who, Caracas barra Los Demonios Rojos say, started the trouble by firing tear gas canisters into the crowd, which included elderly people and children. The barra, two of their members told me, simply decided to defend themselves. It resulted in the match being postponed and the points eventually being handed to the visitors. Caracas' following run of games were played behind closed doors at home and without travelling fans away.

Today, however, at the Estadio Hermanos Ghersi, the only demonstrations from the fans were of colour and noise. Aragua's Los Vikingos barra waved their red and yellow flags, pinned up their trapos (large banners with painted phrases and mottos), and hammered their drums from their central position in the La Popular. For a set of fans derided as poor supporters and without a strong football fan culture, their performance was going some way to disprove that theory. Based in the city of Maracay, so did its alumni.

Jordan (centre) with two leaders of the Los Vikingos barra, Jose (l) and Osmel (r).

Photo: Jordan Florit

Born on 16 May 1980, in Maracay, Juan Arango is considered by many as the best Venezuelan player of all time. He is the record holder for number of appearances for the national team (129) and until Salomón Rondón's brace against the United States in a 2019 friendly he was also the top scorer, with 22. Despite his status in his homeland, Arango missed out on any Venezuelan football league winners medals as he only played six months with Caracas before C.F. Monterrey saw his talent and came calling, leading to a four year spell in Mexico, followed by successful stints in LaLiga and the Bundesliga. La Zurda de Oro, as he is known in Venezuela (the nickname meaning The Golden Left Foot), Arango has an academy in Maracay that carries his name, the Escuela de Fútbol Juan Arango. It was here that a young female footballer named Deyna Castellanos rose to prominence between 2013 and 2016, winning back-to-back South American Championships with Venezuela's U-17s and consecutive fourth place finishes at the World Cup in the same age group. Within a year of leaving the school to start studying at Florida State University, Castellanos finished 3rd in FIFA's World Player of the Year Award despite having never played professionally or for Venezuela's senior team. It is fair to say she is the most well-known Venezuelan female footballer and is tipped to become the best in the world.

Although neither Castellanos nor Arango played any of their professional football in the city of their birth, Aragua FC can boast that Caracas born Salomón Rondón is one of their own. He made his professional debut with the club in Venezuela's top division and aged just 16, in 2006. A year later they won the 2007 Copa Venezuela with Rondón playing the full 180 minutes of the two-legged tie. His success was building. He followed it up with the Venezuelan League's 2007/08 Young Player of the Year Award, which led to a move to Spain's UD Las Palmas. The rest, as they say, is history; history Rondón continues to write, leading the line for the national team as they hope to qualify for their first World Cup.

One tie from that Copa Venezuela winning side to the one that I would watch fall to a 2-1 defeat at the hands of Táchira was their manager, Kike García. He had scored in the 2007 final and was now, despite the loss, on his way to guiding Aragua into the Copa Sudamericana for the first time since his goal had helped them to the Copa Venezuela trophy and thus continental qualification for 2008. Along with touching tributes, bohemian barras, and strapped soldiers, I was witnessing a small piece of Venezuelan football history in the making. As inconsequential as rival fans may deem the club and its barra, the tale they were telling had all the romance that leads us to fall in love with this beautiful game.

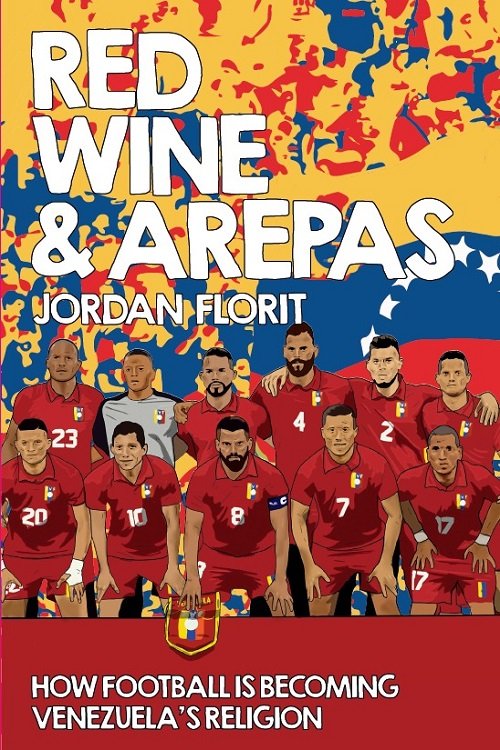

This article was written by Jordan Florit, author of the first English Language book on Venezuelan football, Red Wine & Arepas: How Football is Becoming Venezuela's Religion.

You can follow Jordan on Twitter at @TheFalseLibero, and if you liked this article, Jordan runs a Twitter account dedicated to Venezuelan football, @FUTVEEnglish.

The Red Wine and Arepas book cover.

Photo: Jordan Florit

Tweet